How to start talking about Lord of Slaughter?

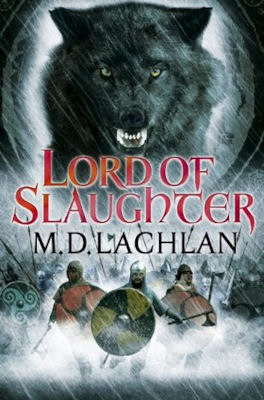

Well, we’ve been here before, of course: this savage, century-spanning saga—of mad gods tormenting mortal men—has played out again and again through the ages. It started, nominally, with Wolfsangel, and continued last year, in Fenrir. Lord of Slaughter, then, is the concluding volume of The Claw, and readers of the series will be relieved to hear it ends as brilliantly—and as blackly—as it began.

“Under a dead moon, on a field of the dead, a wolf moved unseen beneath the rain’s great shadow. The downpour had started with nightfall as the battle ended. There was too much blood for Christ to bear, said the victorious Greeks, and he had decided to wash it away.”

With these words, M. D. Lachlan—a pen-name for British author Mark Barrowcliffe—portends much of what sets Lord of Slaughter apart from its predecessors. In the first, its era and setting, which is to say 10th century Constantinople, make for a moderately more focused and relatable tale that those thus far chronicled in The Claw.

Of late, this great Christian city has been plagued by hellish weather; by cantankerous clouds and gathering thunderheads that the heathen believe the deities of yesterday are responsible for. Amongst themselves they whisper—because to discuss such subjects in public would be an invitation to lifelong imprisonment in the world city’s stinking cellar—they whisper, then, of Fimbulwinter, “the barren and frozen time before Ragnarok, the twilight of the gods. The end of the gods is happening here, so the men say, and the city will fall when it does.”

The Emperor is too busy playing butcher on the battlefield to pay any attention to the malcontents of Constantinople, so his chamberlain Karas takes on the task. He, in turn, solicits the services of an impoverished scholar, Loys, who has only recently arrived in the imperial capital, with an assassin dispatched by his runaway wife’s angered father hot on his heels. Thus, though he fears for his soul, Loys cannot afford to refuse the offer of a protected and elevated place in the palace while he investigates the supposed sorcery plaguing the people—particularly given that he and Beatrice have a baby on the way.

Meanwhile, in the tent of the Emperor, a man wearing a wolf—or a wolf wearing a man, perhaps—appears before Constantinople’s foremost figure. Ragged and ruined, Elifr, or the creature that had been he, presents no threat as yet. The wolfman’s only demand of the Emperor is his own death. Somehow he has become cognisant of the perverse part the fates would have him play in the latest round of the mad gods’ games, and Elifr has no desire to see the show through.

Instead, he’s after an end to it, once and for all eternity: an end to his life, as well as the sickening cycle of heartrending love and awful loss it is intertwined with. However, not one to grand the wishes of unwelcome intruders, be they sent from heaven or the depths of hell, the Emperor has Elifr cast into the lowest level of his city’s subterranean prison to rot… or not.

Last but not least, Lachlan gives us a boy who wishes he were a man—though he is destined to become so much more. As the only witness to the unlikely turn of events that occur in the Emperor’s tent, Snake in the Eye has his overlord’s ear, so when in the pursuit of puberty he commits an offense usually punishable by death, he is only exiled. Later, in Constantinople, Snake in the Eye comes into his own whilst in the employ of a monkish mercenary, who is searching the city for a certain scholar.

Already you can see how Lord of Slaughter‘s expansive cast of characters are poised to come together. And when they do? Why the heavens themselves could not compete with the apocalyptic electricity generated.

“This is the time. This is the needful time. The time of endings. […] Listen, the black dogs are barking. The wolf is near. Can you not hear her call?”

Some of our protagonists are predators, others amongst them their prey, and you will not be able to tell which is which until all is revealed—albeit obliquely—in Lord of Slaughter‘s ghastly last act, when we come face to face, finally, with “King Kill. The back-stabbing, front-stabbing, anywhere-you-like-and-plenty-of-places-you-don’t-stabbing murder god. Odin, one-eyed corpse lord, corrosive and malignant in his schemes and his stratagems. But of course you know all this, you’ve met him before.”

If not, know this: you surely should have done. I fear readers unfamiliar with Wolfsangel and Fenrir are apt to find Lord of Slaughter essentially impenetrable. Newcomers need not apply, unless they’re prepared to go back to where this grimdark Viking saga started.

That said, the brooding books of The Claw have never had a clearer narrative throughline than that offered by the chamberlain’s pet scholar Loys in Lord of Slaughter. As a newcomer to Constantinople, and an investigator whose business it is to unearth an explanation for all the ungodly goings-on that have stilled this thriving Christian city, his perspective soothes like ointment on an injury, or a salve for the soul.

In a sense, then, this ultimate installment is both the least and the most accessible of the three volumes of The Claw. But do not mistake me: Lord of Slaughter is far from light or easy reading. You have to be intimately engaged with the fiction, on every level, to follow along without incident. As per the series’ standard, Lachlan’s prose is awfully involved—dense and intense, on the sentence level it straddles the poetic and the prosaic, demanding and rewarding in equal measure.

In the interim, the medieval metropolis of Constantinople is a pitch-perfect backdrop for this last lament of Loki and Odin; in terms of faith and society and civilisation, it represents a crossroads of sorts, where what was shares a space with what will be, when dark magic is no less likely a factor than science. And that is this book to a T. In this perilous place, at this tumultuous time, one imagines that almost anything is possible.

Lord of Slaughter is in sum as forbidding and ferocious a novel as its darkly ambitious predecessors, and though the barrier for entry is high—thus it is unlikely to earn M. D. Lachlan very many new admirers—it satisfies, and then some, those of us who have followed The Claw from its first fresh yet fetid flush.

And thank the mad gods for that!

Niall Alexander reads and writes about all things weird and wonderful for Tor.com, Strange Horizons and The Science Fiction Foundation. His blog is The Speculative Scotsman, and sometimes he tweets about books, too.